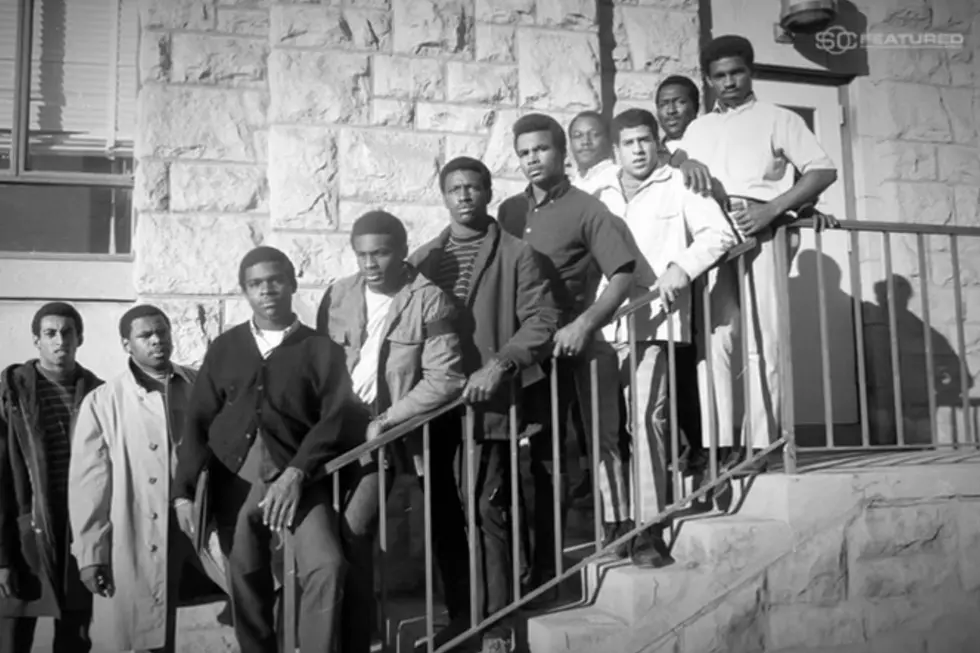

University Honors Black Players Dismissed from Team in 1969

LARAMIE, Wyo. (AP) — Fifty years after 14 black football players were kicked off the University of Wyoming football team for seeking to wear armbands to protest racism, eight of them returned to the Laramie campus to commemorate the anniversary as the school takes another step toward reconciliation.

University officials planned to unveil a plaque at War Memorial Stadium commemorating the so-called Black 14 on Friday. The marker will join an alleyway mural in downtown Laramie that was dedicated last year and cap five days of ceremonies and discussions about the infamous dismissal of all the university's black players in 1969.

They are now being recognized as leaders in the tradition of protest in sport. It's a pantheon that includes U.S. track and field athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who raised their fists on a 1968 Olympics medal podium to protest racism and injustice.

More recently, former San Francisco Giants quarterback Colin Kaepernick accused the NFL of blackballing him for kneeling during the national anthem before games to protest police violence against African Americans.

Protest is appropriate for athletes who want use their fame and visibility to be heard, Black 14 member Tony Gibson said.

"You can judge them any way you want. But when they're saying things that matter, or are trying to draw your attention to things that might need addressing, I think it's very important," Gibson said.

On October 17, 1969, Wyoming head coach Lloyd Eaton summarily dismissed the black football players and revoked their scholarships after they met with him to propose wearing black armbands during an upcoming game against Brigham Young University.

The football players wanted to protest racism some of them experienced in previous games against BYU and how The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints then barred African Americans from the priesthood. Eaton would have none of the idea — and was backed up by the university's board of trustees and Gov. Stan Hathaway.

They never got a chance to mention the armbands before Eaton lit into them about coming from fatherless families and saying they would only be accepted by traditionally black colleges if they weren't at the University of Wyoming, they said.

"Our side is coming out. All these years everybody thought we protested and stuff, and we never did," Black 14 member Ted Williams said.

The healing and reconciliation isn't complete for some of the men who came back to campus this week. Some struggled for years after they were labeled as members of the Black 14.

Lionel Grimes said the episode repeatedly came up during job interviews, and he wondered how many job opportunities he missed because of it. The anger has taken years to overcome, he said.

"I was angry about the fact that I had to pay to go to school. I was angry at how the coach had insulted not only me, my fellow teammates, my ancestry," Grimes said.

Most of all, not being able to learn why Eaton acted as harshly as he did bothers Black 14 members. Eaton could have defused the situation simply by telling the players they couldn't wear the armbands, Grimes said.

"We would've just played football. He never gave us the opportunity to sit down and talk to him," Grimes said. "We were very respectful then."

Wyoming had won the Sugar Bowl the year before and was off to a 4-0 start before that day. The now all-white Cowboys went on to beat BYU and San Jose State but lost their last four games.

After Wyoming finished 1-9 in 1970, Eaton was demoted to assistant athletic director. He died in 2007, leaving the Black 14 without an apology or explanation.

"To me, the disappointment, my greatest disappointment, is I never had a clear understanding of his mindset. I never had a clear understanding of what compelled him to act against, as I understood years later, some of the wishes of his coaches," Black 14 member Guillermo Hysaw said.

Eight of the 14 were starters. Eaton's legacy isn't confined to the Black 14 episode but ruination of the program, Black 14 member John Griffin said.

"He destroyed the Cowboys football team for a decade or so. He is the one who prevented blue-chip players from coming here," Griffin said. "That was on him, not us."

Griffin and some of the others have been back to campus over the decades, including for a 1993 event honoring the best players from each previous decade, but until the past several years reception for the Black 14 was lukewarm, Griffin said.

"Now it's very sincere welcome back: 'We're glad to have you back and we're sorry,' " Griffin said.

More From KGAB